How recording studios contribute to Swindon's music scene

Bands of almost every imaginable genre will play at this year’s Swindon Shuffle. The headliners alone span a variety of genres including the folk duo ‘Fly Yeti Fly’, the alt-rock quintet ‘Modern Evils’ and pop rock quartet ‘All Ears Avow.’ The festival is all set to demonstrate the diversity and creativity of the Swindon scene for the sixteenth year running. It’s certainly worth noting that an abundance of artists are based here, all singing about different themes in stylistically very different ways. There’s a solid network of studios and rehearsal spaces here too. They all keep the Swindon scene buzzing, situated as it is on an important spot of the M4 corridor, between two UK musical capitals: London and Bristol.

I was eager to discover, while writing for The Ink Swindon, exactly how the Swindon scene works. How do producers and their studios uplift younger bands? How do they give established bands a boost? These were the questions that I asked myself and they led me to some interesting places, not least my first experience of the Magic Roundabout. The main thing, overall, was that I met three of the most renowned music producers in-and-around Swindon. Each person that I spoke to had an illuminating perspective on the Swindon scene. Each of their recording spaces offered something different; a unique approach. It became clear that there’s no shortage of options for Swindon artists looking to tap into the magic of music production. Even I, with my limited experience as a performing musician, could appreciate it.

Interestingly enough I first met two members of the aforementioned ‘All Ears Avow’. Claire and Sean, when they’re not singing and playing drums in their band, run ‘Western Audio’: a studio near Rivermead Skate Park in Westmead. A few years ago, an indie band based at my old secondary school recorded some songs with Claire and Sean. Both of them remembered the band, having taught most of them at a music academy (yet another aspect of their impressively packed schedules). I was interested to know if their teaching experience had proved useful in working with younger bands.

Speaking as the head engineer, Claire said: ‘Well there’s a lot of psychology involved in recording bands, regardless of their age. Lots of people might think that they know a lot, despite their inexperience. So you’ve got to manage people in a gentle way, and allow them to push through with their creative ideas. It’s a guiding process of saying “That’s cool but what about this?” Like planting new seeds. It’s definitely a lot like teaching.’

Sean remarked: ‘I’ve always thought that you’re good at that, from sitting in on your sessions. You’re definitely good at managing personalities and getting the very best out of people.’

There’s a very self-assured and confident tone to music produced at Western Audio, no matter how young and up-and-coming the artist might be. This is certainly the case with the Swindon-Birmingham-formed band ‘Heriot’, who formed, in their current iteration, in 2019. Over the past two years, they’ve become one of the most exciting new names in the UK metal scene, while recording often at Western Audio. I learned from Claire that there’s an abundance of young bands like this in Wiltshire, with an intense will to succeed.

‘There’s been quite a boom since the pandemic,’ she said. ‘With the younger generation going through college and finishing secondary school, locked in their houses, and not being able to embrace life and stuff, they’re now getting out there. I think it’s a bigger step than people give them credit for. Especially from an anxiety point of view.’

‘So yeah, there’s lots of young bands appearing. People want to get together and do group activities. There’s a great support network too: all the local venues are up for supporting the scene.’

‘We see it here and see it when we gig locally’ Sean added. ‘Suddenly there’s all these new faces.’

Sean and Claire are both passionate about the idea that the local scene has flourished in recent years. They also both expressed a sense of responsibility towards it.

Claire explained: ‘Our background is being an independent band, and we’ve needed support over the years. So in our work, we want to grow and provide support for other artists. It’s important to us. We’ve played gigs, toured and taught younger bands. We’re always up for getting involved more.’

I asked what makes a successful studio session. Claire replied: ‘People being relaxed and not watching the clock. It needs to be as comfortable an environment as possible. If people are getting stressed out, we say “Take a moment. Go play the snares for a bit.” We’ve also got a games console. We strive for this to feel like a creative space, and not like you’re coming to work.”

These words were indicative of the duo’s recording ethos. They’re both very lovely and forward-thinking people, intensely invested in the creative potential of their clients. Meeting two musicians so positive about their local scene made me feel very positive about the future of independent music.

Next, I met John Buckett, who echoed this sentiment. He kindly welcomed me to his recording space: Earthworm Studios in Marshgate, and explained the way by which he understands the local scene. At the time, we were sitting beside his sci-fi-esque mixing desk and his airy rehearsal room was next door.

‘I’ve had some clients coming to this studio for fifteen years,’ John said. ‘They want to escape to it, in a social way, because it’s important to them. Over lockdown, a few people that I knew weren’t doing too well, while locked into their houses. So, I stayed open to vulnerable people, when I could have stayed shut. And that’s what studios have always done. I think Swindon is a very talented town. It’s my town too, of course. But I have clients all around the south-west of England, and Italy, America and Australia; all sorts of places. So my work is a many-and-varied thing. I wouldn’t want to put up barriers for who I work with.’

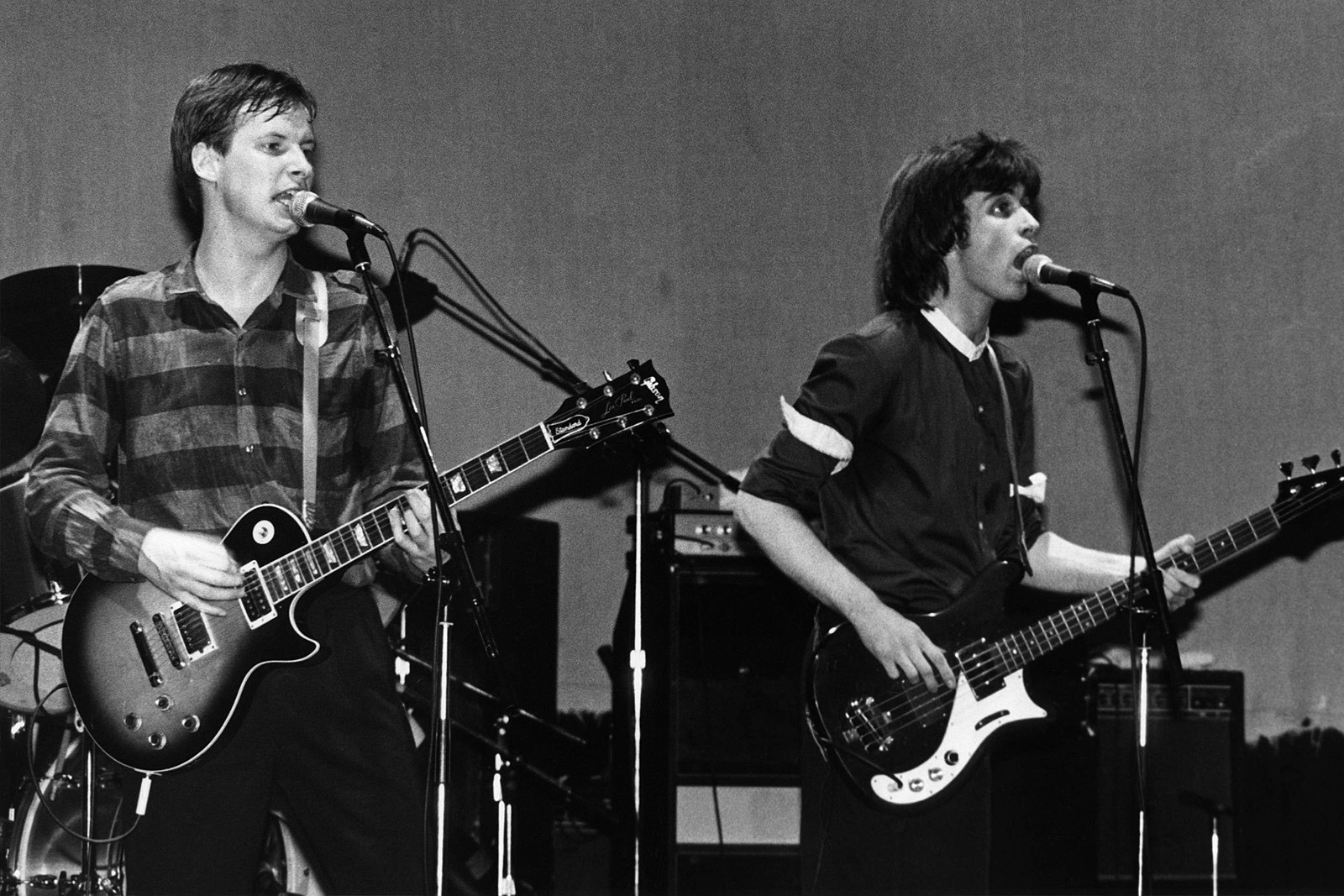

John’s list of production and instrumental credits is certainly staggering. He’s worked with Netflix, the BBC and NATO, as well as an array of artists, like Gaz Brookfield, Littlemen, Innes Sibun, Anton Barbeau and also half of XTC: Terry Chambers and Colin Moulding, the latter of whom John’s known since he was young.

‘I became friends with his son when we were school kids, and we were in a band together. I have my first memory of Colin standing at the back of a rehearsal studio in Wanborough, not looking particularly impressed with our efforts! So I always knew him as my mate's Dad, before I knew him as a musician.’

I was struck, overall, by John’s tremendous openness, both personally and in his collaborative methods. He strives to comprehensively understand how somebody envisages their creative project, before he helps to bring it to life.

‘If you get a singer-songwriter, by and large, they want a realisation of their songs,’ he said. ‘My job then, isn’t to get really heavily involved in the songwriting. You ask what they hear in their head and then it’s down to me to hire the right musicians who I think will be sensitive to the project, and do it within budget and within time. That differs from a band, because the dynamics are different, and more complex, often with young bands. With a band you’re trying to understand the realisation of a collective vision and making sure it’s clear in the first place, knowing what you’re all aiming for, what the record’s for and who it’s for.

His openness to others means that the ‘personal’ aspect of production is now more important to him than the technical. He reflected: ‘ I’ve been doing this long enough that getting good recorded sound is a simpler part of the job for me now. If musicians have gone away, and got a smile on their face and they’re looking forward to the next recording session with positivity, motivation and drive, then that’s success.’

I then asked John if there’s any type of projects that he would like to work on more often. ‘Crikey,’ he replied, ‘I’ve done ambient, jazz, musical theatre, metal and indie, whatever that is. I’m trying to think of something I haven’t done. I wouldn’t mind if someone phoned me up and said that they needed to record a 50 piece orchestra. I wouldn’t mind that. I’ve recorded a string quartet here, but it’d be nice to do a straight up classical record.’

These days, open and contemplative ways of producing are perhaps few and far between; in a time when speed, efficiency and making money are often prioritised by the music industry. Nick Beere, the owner of Mooncalf Studios on the Marlborough Downs, seemed to typify this view. I phoned him on a sunny evening in late July, while he was holidaying in Scotland. He described what he strives for, as a producer:

‘I try to get people to “sound like them”,’ he said. ‘Some producers have a specific sound in their head, which they try to impose upon people with no compromise. I always ask “does it sound good?” rather than “does it sound how I expected it to?”. But then again, people might sometimes turn to me, at the end of sessions, and say: “that’s exactly what I had in my head.” And that’s the best thing in the world. That’s when I know that I’ve done it. So I do have a certain way of working. But it’s not something I think about. It’s just what I do.’

Nick built Mooncalf Studios himself, after working for over twenty years at Stable Studios, in Aldbourne. It was a labour of love, a remote location where Nick can commit to what he loves, working with a colourful array of clients, including Justin Hawkins of The Darkness. He certainly wasn’t keen to elaborate upon its location, considering how vulnerable and remote it is. For him, it’s a haven where, through collaboration, he can be true to his own capabilities, while making music in a less-is-more kind of way.

He explained: ‘Some might ask “how long does it take to get a drum sound?” Well it takes as long as it takes to bring up the faders and set up the mics. You don’t need the most expensive mics in the world to get the best drum sound. I’ve heard some incredible recordings done with inexpensive mics, I’ve used expensive ones and got average results from them. Some people put emphasis on having all the gear: ten compressors, whatever. There’s a singer-songwriter that I recorded with in the 80s. During lockdown, I dug up some recordings that we did, and put them through some mastering software. He’s signed to a small label in New Zealand, and they released those recordings. They sounded great too, even after 30 years.’

Nick’s career as producer has been a storied one, through which he’s seen huge change in the music industry. He’s seen the rise of digital recording; and countless bits of technology designed to maximise speed and efficiency. He explained that he’s an analogue kind of man, for these reasons.

‘Nowadays you have apps on your phone which can do what you’d need a million pound studio, in the 70s/80s to do. That’s how far we’ve come. I consider myself lucky in that I went through the analogue phase. In 1995 I got my first digital editing software. Up until then you had to edit something with a razor blade and a splicing block. Remixing could take hours. When you’re working on tight budgets you don’t have flexibility. Nowadays you click, load and recall files in seconds. To recall a mix in the 90s was hours and hours of work. It’s easy to forget that.’

My chat with Nick seemed representative of my whole investigation. Nick owns an off-the-beaten-track kind of studio, which eschews the fast-moving technology of the broader industry. He focuses instead upon how the producer-musician relationship can be made as productive as possible.

This outlook was expressed, more-or-less, by each producer that I met. They all strive to develop and provide for the vision of their clients, rather than vice versa. It’s clear these aspects of the Swindon scene are conducive to something pretty magical and the Swindon Shuffle’s certainly going to reaffirm that. Long may it all continue.

Post a comment